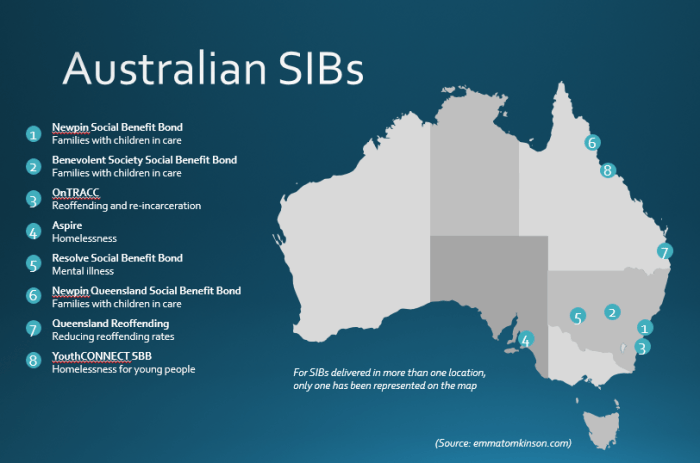

There have been eight social impact bond (SIB) contracts signed so far in Australia (I use this definition). Social impact bonds began being referred to as ‘social benefit bonds’ in the state of New South Wales in 2011. This was due to a new Government wanting to continue the previous Government’s social impact bond policy, but put their own stamp on it. The term has also been used by the Queensland Government.

There have been eight social impact bond (SIB) contracts signed so far in Australia (I use this definition). Social impact bonds began being referred to as ‘social benefit bonds’ in the state of New South Wales in 2011. This was due to a new Government wanting to continue the previous Government’s social impact bond policy, but put their own stamp on it. The term has also been used by the Queensland Government.

SIB processes have been led by state governments

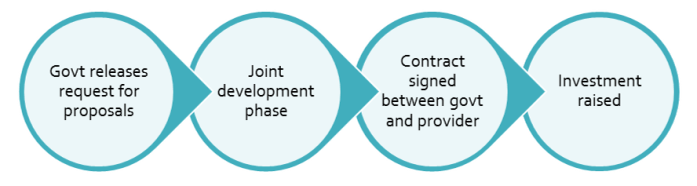

All social impact bonds in Australia have been initiated by state governments. Four of Australia’s six state governments have signed SIB contracts or are in the process of developing them. Each of these governments has pursued their SIB contracts by releasing an open request for proposals. New South Wales has released four that can be accessed here.

The requests for proposals have resulted in service providers being chosen, sometimes in partnership with financial intermediaries or other parties. They then enter what is referred to as a ‘joint development phase’ where the feasibility and details of contracts are established. Large not-for-profits in Australia are much larger and deliver across a wider range of services than in the UK, so they have the capacity and experience to negotiate directly with government, rather than through an intermediary. Many of these organisations generate millions of dollars income from government contracts annually, so are very experienced in government negotiations. The joint development phases have resulted in outcomes-based contracts between the state government in question and their chosen not-for-profit service providers. Not all projects that have entered this joint development phase have exited, with some projects deemed infeasible. It is worth noting that the first two SIBs have made changes to their payment metrics after observing them in practice.

Investors

Five out of the six social impact bonds in Australia have raised funds on the open market, following the process above. This has resulted in a greater number and range of investors than SIBs in other parts of the world. Investors include trusts, foundations, institutions (including superannuation/pension funds), charities and high net worth individuals. Individual investment is restricted to ‘wholesale’ investors. A wholesale investor is a finance professional or a ‘sophisticated investor’ i.e. one who has an income of over AU$250,000 per annum for the last two years or assets in excess of AU$2.5 million. An offer restricted to wholesale investors safeguards retail investors from buying products they do not sufficiently understand and is cheaper to issue. The minimum investment for all SBBs has been AU$50,000. All SIBs have been oversubscribed, with the most recent round for NSW mental health and Queensland’s OOHC SIBs reaching their target in one month. One SIB, OnTRACC, is privately financed by a bank and service provider. There are links to the information memoranda of several SIBs in the details below. These documents provided the information for investors considering investment.

Intermediary roles

In some SIBs, intermediaries have only been involved in raising and managing investment, and are thus referred to as ‘financial intermediaries’. For other SIBs, they have been instrumental in program design and contract negotiation. But we haven’t seen them assume the roles of performance management or conducting ‘feasibility studies’ as is common overseas.

Attracting investment

Government initiating the SIB process has led to the general perception that SIBs save governments a lot of money, and that governments should be actively enticing providers and investors to participate by sharing some of those savings.

Because the contract is signed before investors are sought, there is a need to make the SIB attractive to investors. If investors don’t sign up, the new service won’t happen and years of work is wasted. So this leads to a range of efforts to make the investment attractive that we haven’t seen elsewhere.

- Most Australian SIBs include a ‘standing charge’, where government pays a fixed amount (which can be up to 50% of contract value) regardless of outcome. In many other SIBs around the world, government payments are only made in response to outcome achievements. This was used in the Benevolent Society Social Benefit Bond to create a ‘guarantee’ of Principal for one tranche of investors.

- There are exit or termination points for investors, so that the program can be terminated if early results are not good, and the unspent proportion of the investment returned.

- Rates of return to investors are capped much higher than overseas – the maximum rate of return for one tranche of the Benevolent Society SBB is 30% IRR, in comparison to Peterborough’s 13% and Belgium’s 6%.

- Metrics were created that limited risk for investors. For example, the Newpin Social Benefit Bond funds separate programs for mothers and fathers, but as the fathers’ program had less evidence, it wasn’t included in the payment metric for investors. The fathers’ program was included in the payment metric for the charity providing the services.

- The media has been used to promote SIBs as an investment opportunity, with coverage of each investment opportunity including the national financial newspaper, the Australian Financial Review.

The eight SIBs – details and references

This information is provided to make it easier for researchers and other interested parties to access the range of information on Australian SIBs. It is all copied as faithfully as possible from original sources, but the original sources are still more reliable. The eight SIBs are listed in chronological order below, but are grouped by state below that. Clicking on the name of each SIB will take you to the information about it.

| Chronological order | Social Impact Bond (State) | Status |

| 1 | Newpin Social Benefit Bond (NSW)

Families with children in care |

Currently delivering services |

| 2 | Benevolent Society Social Benefit Bond (NSW)

Families with children in care |

Currently delivering services |

| 3 | OnTRACC (NSW)

Reoffending and re-incarceration |

Currently delivering services |

| 4 | Aspire (SA)

Homelessness |

Currently delivering services |

| 5 | Resolve Social Benefit Bond (NSW)

Mental illness |

Investment raised, yet to begin delivering services |

| 6 | Newpin Queensland Social Benefit Bond (QLD)

Families with children in care |

Investment raised, yet to begin delivering services |

| 7 | Queensland Reoffending (QLD)

Reducing reoffending rates |

Contracts signed, yet to raise investment. |

| 8 | YouthCONNECT SBB (QLD)

Homelessness for young people |

Contracts signed, yet to raise investment. |

New South Wales

Newpin Social Benefit Bond

(Source: NSW Office of Social Impact Investment)

| Location | Expanding from 4 to 7 locations throughout NSW |

| Service start date | July 2013 |

| Duration | 7 years |

| Social Issue | Restoring children from out-of-home care to their families and supporting families to prevent children entering care |

| Target population | 700 families; more than half of which have at least one child aged six or under in out-of-home care |

| Outcome metric | The restoration of children from out-of-home care to their families. All family restorations are independently decided by the NSW Children’s Court. |

| Outcome evaluation method | The outcomes are compared to a live control group (for the first three years the comparison was an actuarial estimate). |

| Intervention | Parents attend Newpin centres at least two days a week over 18 months. In this time, they are supported to develop their parenting skills, attend therapeutic support groups and interact meaningfully with their children. |

| Service Provider | Uniting |

| Outcome Funder | Department of Family and Community Services NSW |

| Upfront capital commitment (by investors) | $7m (total expected Government payments $47m) |

| Investors | 59 wholesale investors + 1 retail investor, includes NG Super, Christian Super, Uniting (service provider), The Benevolent Society (charity), Emma Tomkinson (retail investor) |

| Other roles | Financial intermediary: Social Ventures Australia |

| Maximum loss and return for investors | Minimum Interest Rate = 5% p.a. over the first three years.

Maximum Interest Rate = 15% p.a. over the full term. Maximum loss is 50% of Principal at the maturity date. |

| Payment schedule and thresholds | Interest payments made annually. Principal Repayment repaid on the Maturity Date if the Restoration Rate over the full term is greater than 55%. |

| Investor payment dates | 30 June 2014 (calculation date. Actual payments made later that year) |

| Results so far | Newpin’s overall restoration rate for the first three years is 61 per cent, compared to 25 per cent for similar families with at least one child under the age of six that were not part of the program. Based on this performance, investor returns were 12.2 per cent for the first three years. |

Sources and references:

Newpin Factsheet (June 2017 – by NSW Office of Social Impact Investment)

Information Memorandum for prospective investors (April 2013 – by SVA)

The Benevolent Society Social Benefit Bond

| Location | NSW | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service start date | 2013 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duration | 5 years | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Social Issue | Preventing children entering out-of-home care | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Target population | Up to 400 families who are expecting a child or have at least one child under six years of age (approximately 636 children), and who have been reported to Department of Family and Community Services as being at risk of significant harm. There are four annual cohorts, which will be used to calculate payments. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome metrics | Three key measures:

· Out-of-home care entries · Helpline Reports from six months after entry to the service · Number of safety and risk assessments A calculation is made using the three measures, and then adjusted for children that cannot be matched to the control and shortfall in referrals. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome evaluation method | Results are compared to a live control group and independently certified. Outcome measurements are taken throughout the investment and comparisons calculated annually. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Intervention | Practical and therapeutic in-home support to at-risk families for up to 12 months, including 24/7 support during the first 12 weeks. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service Provider | The Benevolent Society | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome Funder | Department of Family and Community Services NSW | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Upfront capital commitment (by investors) | $10m (total cost of intervention $12.75m) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Investors | Equity tranch: $2.5m from 17 investors

Principal protected tranch: $7.5m from 40 investors including NRMA Motoring & Services, Australian Ethical Investments, The Benevolent Society, Westpac Bank and Commonwealth Bank of Australia. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other roles | Financial intermediaries – Westpac Banking Corporation and the Commonwealth Bank of Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum loss and return for investors | Equity tranch: all capital at risk with maximum 30% return

Principal protected tranch: 100% capital guaranteed with maximum 10% return |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Payment thresholds |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Investor payment dates | There is only one investor repayment – at the end (late 2018) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Results so far | 2016 results showed that 21 per cent fewer children entered care compared to a control group. Investor returns will be calculated and paid after the bond ends. If returns were paid based on third year results, principal protected investors would receive a six per cent return and equity investors would receive a 10.5 per cent return |

Sources and references:

The Benevolent Society Social Benefit Bond Factsheet

Benevolent Society 2016 Investor Report

Information memorandum for prospective investors, summarised in Presentation to investors

OnTRACC

This contract is not referred to as a Social Benefit Bond by the NSW Office of Social Investment, however it fits the definition I use, so I’m including it here.

| Location | Selected Sydney metropolitan areas |

| Service start date | September 2016 |

| Duration | 5 years |

| Social Issue | Parolee re-offending |

| Target population | Up to 3,900 adult parolees with a medium to high risk of reoffending, released to supervision in selected Sydney metropolitan areas |

| Outcome metric | Reduction in the re-incarceration rate of participating parolees in the 12 months after their release |

| Outcome evaluation method | Participating parolees reoffending and re-incarceration will be compared to a randomly selected control group |

| Intervention | The program provides participating parolees with enhanced support and referral services for up to 12 months following their release. |

| Service Provider | Jointly delivered by the Australian Community Support Organisation (ACSO) and arbias |

| Outcome Funder | Corrective Services NSW |

| Upfront capital commitment (by investors) | Unknown |

| Investors | Australian Community Support Organisation (ACSO) and NAB |

| Other roles | Calculation of outcome metric: NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (BOCSAR) |

| Maximum loss and return for investors | Unknown |

| Payment schedule and thresholds | Unknown |

| Investor payment dates | Unknown |

NSW Office of Social Impact Investment OnTRACC Fact Sheet

Resolve SBB

| Location | Western NSW and Nepean Blue Mountains | ||||||||||||||||||

| Service start date | Expected October 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Duration | 7.75 years | ||||||||||||||||||

| Social Issue | Mental illness | ||||||||||||||||||

| Target population | Approximately 530 mental health patients in Western NSW and Nepean Blue Mountains local health districts | ||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome metric | Percentage reduction in National Weighted Activity Units (NWAU – an activity measure for determining total health related service consumption, which also accounts for the severity and duration of services consumed, including hospital admissions) incurred by the individuals in the program over their two-year measurement periods relative to those incurred by a control group | ||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome evaluation method | Results will be compared to a live control group | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intervention | A residential program for periodic crisis care, community outreach support and a 24/7 “warm line” offering after hours phone support to provide advice and support before a crisis situation arises.

Each individual will receive recovery-orientated support for up to two years lead by peer workers who have a lived experience of a mental health issue. |

||||||||||||||||||

| Service Provider | Flourish Australia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome Funder | NSW Health | ||||||||||||||||||

| Upfront capital commitment (by investors) | $7 m (total expected Government payments $21.7m; possible range is $9m to $23.9m) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Investors | The 50 investors range from high net worth individuals and foundations, through to institutional investors such as NGS Super and Grosvenor Pirie Super. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Other roles | Financial Intermediary – Social Ventures Australia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum loss and return for investors | Termination rights limit downside loss to approximately 40% of principal. Returns are 2% pa fixed interest payments over 4.75 years, then performance coupons based on the level of Resolve SBB Trust assets to a maximum of 11% per annum IRR over the 7.75 years. | ||||||||||||||||||

| Payment schedule and thresholds |

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Investor payment dates | 31 March 2019 (final coupon 31 March 2025) |

Sources and references:

http://www.socialventures.com.au/work/resolve-sbb

Resolve SBB Information Memorandum (PDF, 1MB)

Resolve SBB Deed Poll and Purchase Deed (PDF, 1MB)

South Australia

Aspire Social Impact Bond

| Location | Adelaide metro | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service start date | 1 July 2017 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duration | 7.75 year bond term. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Social Issue | Homelessness | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Target population | Approximately 600 individuals will be referred to the Aspire Program from across Adelaide over a four year period. 400 of those referred are expected to meaningfully engage in the program. Referrals will be accepted from providers of homelessness services, participating prisons (up to 10% of referrals), participating hospitals (up to 10% of referrals) and Housing SA. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome metric | Use of health services (hospital bed days), justice services (convictions) and homelessness services (short term and emergency accommodation periods) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome evaluation method | Health, justice and homelessness service use compared to historical baseline | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Intervention | Based on the ‘housing first’ intervention model, with a focus on strengthening community engagement and employment participation. Participants will be provided stable accommodation, job readiness training, pathways to employment and life skills development. They will also have the long term support of a dedicated ‘Navigator’ to help them connect with wider support services and identify and achieve their aspirations. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service Providers | Hutt St Centre, an Adelaide based homelessness services specialist, in partnership with community housing providers including Housing Choices SA (formerly Common Ground Adelaide) and Unity Housing. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome Funder | Government of South Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Upfront capital commitment (by investors) | $9m (total Government payments if target is met $17m; possible range is $6m to $21m) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Investors | 65 investors including NGS Super, Future Super and HESTA, Coopers Brewery Foundation | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other roles | Financial intermediary: Social Ventures Australia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum loss and return for investors | Returns are via 2% pa fixed interest payments over 4.75 years, then a performance coupon is paid that could take the IRR of the SBB to a maximum of 13% over 7.75 years. The maximum potential loss of Principal is approximately 50% due to termination rights. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Payment schedule and thresholds |

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Investor payment dates | Payments calculated annually 31 December 2018 -2024 |

References: https://probonoaustralia.com.au/news/2017/03/homelessness-social-impact-bond-raises-9m/

http://www.socialventures.com.au/work/newpin-qld-sbb/

Aspire SIB Information Memorandum (PDF, 2MB)

Aspire SIB Deed Poll, Purchase Deed and Note Issue Supplement (PDF, 993KB)

Queensland

Information on Queensland SBBs is published by the Queensland Government here https://www.treasury.qld.gov.au/growing-queensland/social-benefit-bonds-pilot-program/

Newpin Queensland SBB

| Location | Cairns and two other locations in Queensland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service start date | Beginning 2018 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Duration | 7.25 years | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Social Issue | The over-representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children in out-of-home-care | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Target population | Approximately 200 primarily Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander families who have at least one child aged under five and a half years old and is in OOHC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome metric | The number of children in the Intervention Group that have been, and continue to be, reunified with their parent(s) [from out of home care] 18 months after their referral to the Newpin Program, less the Counterfactual Reunifications | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome evaluation method | Comparison against historical baseline | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Intervention | Parents attend Newpin centres at least two days a week over 18 months. In this time, they are supported to develop their parenting skills, attend therapeutic support groups and interact meaningfully with their children. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Service Provider | UnitingCare Queensland | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Outcome Funder | Queensland Government | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Upfront capital commitment (by investors) | $6m (total expected Government payments $26.5m) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Investors | 34 investors, including NGS Super, along with QIC and HESTA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other roles | Financial intermediary: Social Ventures Australia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Maximum loss and return for investors | Returns are via 2% pa fixed interest payments over six years, with a performance interest payment in year 7 that could take the IRR of the SBB to a maximum of 12% over 7.25 years. The maximum potential loss of Principal is 12% during the first three years and 50% thereafter. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Payment schedule and thresholds |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Investor payment dates | 30 September each year from 2018 to 2024 |

References: https://s3.treasury.qld.gov.au/files/sbb-newpin-qld-fact-sheet.pdf

https://s3.treasury.qld.gov.au/files/sbb-update-march-2017.pdf

http://www.socialventures.com.au/work/newpin-qld-sbb/

Newpin Qld SBB Information Memorandum (PDF, 2MB)

Newpin Qld SBB Deed Poll and Purchase Deed (PDF, 1MB)

Youth Choices

The Queensland Government has signed a contract with Life Without Barriers for this SBB. Funds have not yet been raised.

| Location | Two locations – one in North Brisbane and the second in South Brisbane. |

| Service start date | Expected start date late 2017 |

| Social Issue | Reducing offending rates for Young Queenslanders |

| Target population | Up to 600 young people, 10-16 years old, who have been determined to have ‘high to very high’ risk of reoffending will be referred to the program by Youth Justice over five years. |

| Intervention | Multi-Systemic-Therapy – will work with the family unit to deliver improved family functioning and parenting skills, higher rates of school participation and reduce substance abuse. |

| Service Provider | Life Without Barriers |

| Outcome Funder | Queensland Government |

| Other roles | Financial intermediary: National Australia Bank (NAB) |

References: https://s3.treasury.qld.gov.au/files/sbb-update-may-2017.pdf

YouthCONNECT SBB

The Queensland Government has signed a contract with Churches of Christ in Queensland for this SBB. Funds have not yet been raised.

| Location | Two services – one in South East Queensland and the other in Townsville. |

| Service start date | Expected late 2017 |

| Social Issue | Homelessness for young people |

| Target population | Young people aged 15 to 25 who are exiting or have exited statutory care and are homeless or are at risk of homelessness |

| Service Provider | Churches of Christ in Queensland |

| Outcome Funder | Queensland Government |

| Other roles | Intermediary (raising and managing investment, program design and negotiations): Social Outcomes, in conjunction with Westpac |

Victoria

Two contsortia, led by Anglicare and Sacred Heart Mission, have been selected to jointly develop social impact bonds with the Victorian Government. Service contracts have not yet been signed.

- The Anglicare consortium, which includes VincentCare, proposes a mix of individualised case management, specialist support, and stable housing to improve outcomes for young people leaving out of home care.

- Sacred Heart Mission will provide rapid access to stable housing and intensive case management to support Victorians experiencing chronic homelessness and harmful alcohol and other drug use.

http://www.premier.vic.gov.au/first-social-impact-bonds-for-disadvantaged-victorians/

I am more than happy to be corrected on any of the above – please email with changes that should be made, or or comment with differences of opinion or relevant information.

One of my key lessons from my Newpin practice colleagues was the importance of their relationships and conversations with government child protection (FACS) staff when determining which families were ready for Newpin and had a genuine probability (much lower than 100%) of restoration. When random allocations were first flagged I thought ‘this will bugger stuff up’.

One of my key lessons from my Newpin practice colleagues was the importance of their relationships and conversations with government child protection (FACS) staff when determining which families were ready for Newpin and had a genuine probability (much lower than 100%) of restoration. When random allocations were first flagged I thought ‘this will bugger stuff up’. n program to ‘get’ a SIB and that we were thinking ethically through all aspects of the program. We were a team and all members knew where they did and didn’t have expertise.

n program to ‘get’ a SIB and that we were thinking ethically through all aspects of the program. We were a team and all members knew where they did and didn’t have expertise.