There are many ways to procure for a SIB. The following examples of procurement processes have been chosen to demonstrate variation. The advantages and disadvantages of each are context specific – if you are developing a new procurement process you might want to think about whether each variation promotes or hinders your objectives.

I the word ‘procurement’ to refer to any of the means by which governments might ask external organisations to deliver a service under contract.

Please refer to the source information if you are producing further publications – I have tried to faithfully summarise each procurement process, but my interpretations have not been checked with the parties involved. Happy to accept corrections or suggestions.

Ontario, Canada

Deloitte won the initial RFP is currently in the final stages of that contract, with an Ontario Government decision expected in the next few months. An interesting feature of this process is the parallel ‘internal’ and ‘external’ streams, where public servants are proposing their outcome ideas at the same time as people in the market are also proposing. External ‘registrations’ of interest were called for in the following priority areas:

- Housing – Improving access to affordable, suitable and adequate housing for individuals and families in need.

- Youth at Risk – Supporting children and youth with one or more of the following: overcoming mental health challenges, escaping poverty, avoiding conflict with the law, youth leaving care, Aboriginal, racialized youth, and other specific challenges facing children and youth at risk, for example employment.

- Employment – Improving opportunities for persons facing barriers to employment, including persons with disabilities.

New South Wales, Australia

In New South Wales we suffered from locking ourselves out of developing the idea with organisations over the 6 months it took to run RFP and negotiate the contracts for the next stage. We did not agree a maximum budget or referral mechanism until the joint development stage – we asked for organisations to come up with these as well as a full economic and financial model in their RFP. None of us who were involved in designing the procurement process feel we got it quite right, yet given the opportunity, we would all redesign it in different ways! (See NSW Treasury page on ‘Social Benefit Bonds’)

Procurement timeline:

| November 2010 | NSW Government commissions a feasibility study from Centre for Social Impact |

| February 2011 | SIB Feasibility Study report submitted and published |

| March 2011 | State government elections and change of government (left to right) |

| September 2011 (due Nov) | SBB Trial Request for Proposal released |

| March 2012 | 3 consortia announced joint development phase begins |

| March 2013 | Newpin Social Benefit Bond contracts agreed |

| June 2013 | Benevolent Society + 2 banks Social Benefit Bond contracts agreed |

New York City, USA

An interesting feature of the New York City SIB development process was that service delivery partners were procured for first, and started delivering services while being involved in developing a SIB for future financing of the service.

New Zealand

The New Zealand process appears to be the only one where the government procured for the intermediaries and service providers separately. It is not yet clear what the benefits of this might have been or how they will be matched up.

Massachusetts

Several US states have followed a similar procurement process to Massachusetts, which first involved a Request for Information from organisations external to government. This approach allows the market to shape government thinking and recognises that there may be social issues and intervention types that government hasn’t previously considered. Some jurisdictions have accomplished this with less formal consultations e.g. Queensland Government’s cross-sector payment-by-outcomes design forum and Nova Scotia Government’s cross-sector SIB Working Group.

Massachusetts Selection Criteria:

- Government leadership to address and spearhead a public/private innovation.

- Social needs that are unmet, high-priority and large-scale.

- Target populations that are well-defined and can be measured with scientific rigor.

- Proven outcomes from administrative data that is credible and readily available in a cost effective means.

- Interventions that are highly likely to achieve targeted impact goals.

- Proven service providers that are prepared to scale with quality.

- Safeguards to protect the well-being of populations served.

- Cost effective programs that can demonstrate fiscal savings for Government.

Department of WOrk and Pensions UK

The Department of Work and Pensions developed a ‘rate card’ for payment per individual outcome for their procurement. They asked organisations to choose a subset of outcomes to deliver, nominate a price per outcome and the intervention that would achieve them. A social impact bond structure was not mandated – seven out of the ten chosen programs involved external investors. The following process occurred twice in 2012:

DWP Rate Card: DWP pays for one or more outcomes per participant which can be linked to improved employability. A definitive list of outcomes and maximum prices DWP was willing to pay for Round 2 is:

Saskatchewan, Canada

This process may be followed if an unsolicited proposal is received. An interesting feature of the Saskatchewan SIB is that the investor has also signed the contract with government.

Essex, UK

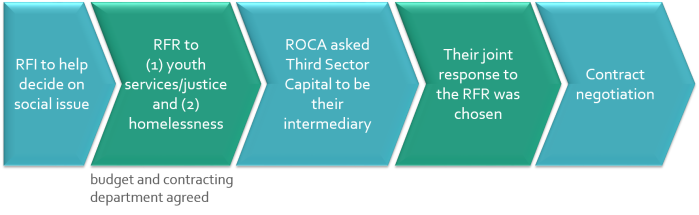

The process of developing the Essex social impact bond is described in Social Finance’s Technical Guide to Developing Social Impact Bonds. Social Finance worked closely with Essex County Council to research and develop a SIB, with the final step being procuring for a service provider.

Conclusion

Governments need to think about which information need to be included in a procurement document. For example, if it is desired that organisations external to government come up with completely new service areas, then a procurement process that does not state the social issue to be addressed or contracting department might be suitable. But information and constraints that are known should be included in a tender document. It’s simply irresponsible to have a criminal justice organisation spend time working on a response offering intensive services for 30 female offenders if there was never any possibility the SIB was going to be in justice, or with female offenders, or with a small group of people.