In many discussions about social investment in Australia, someone expresses the idea that we are 10 years behind the UK, with the implication that if we do everything they have done, we will catch up. But the landscape for social purpose organisations and investment differs between the two countries, and we need to think clearly about the context behind UK Government policy and adapt, rather than adopt their initiatives in Australia.

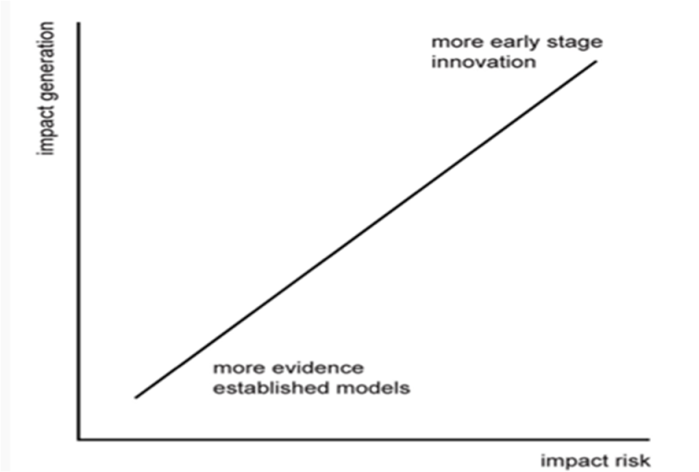

Dan Gregory, in his paper Angels in the Architecture, made a useful distinction between definitions of social investment as that which is (a) about social sector organisations accessing finance, and/or (b) about increasing the social impact of finance. The majority of Cabinet Office policy falls fairly squarely in the first category, but Australian efforts so far heavily involve the second.

Why UK initiatives don’t always fit the Australian context

- Australian social sector organisations include much larger, more powerful organisations that deliver across a wider range of services in the UK. In the UK, the largest charities are almost fully funded by philanthropic donations, whereas in Australia big charities are largely funded through delivering government contracts.

- Australia has avoided the recession and resulting austerity that has gripped the UK and many of their European neighbours since 2008. Thus our investors and investment vehicles are, by comparison, healthy and attractive.

- The UK has a large (over 100 staff) Office for Civil Society situated in the Cabinet Office that is responsible for strong, centralised policy for the sector. This is in addition to their Charities Commission and has resulted in a range of policy initiatives that have led to the UK being labelled leaders in this area. Australia’s Office of the Not-for-Profit Sector that was part of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet will be disbanded under an order signed on 18 September 2013.

- In the UK, the ‘social enterprise’ identity is assumed by far more organisations than in Australia. Many organisations in Australia that fit within definitions of social enterprise do not use the term, although it is becoming more popular.

This does not mean that social investment policy initiatives in the UK will not produce benefits if applied in Australia, but it does mean that we should only attempt a translation of initiatives where the implications, costs and benefits in the Australian context fall in our favour. A replication of initiatives accompanied by the expectation of replicated results will only lead to disappointment.

Summary of recommendations

A blow-by-blow analysis

1. Investment readiness program (Investment and Contract Readiness Fund + Social Incubator Fund)

The Investment and Contract Readiness Fund (ICRF) is a 3-year, £10m fund that provides grants of between £50,000 and £150,000 to ambitious social ventures, with the potential for high growth. These grants are used to purchase tailored capacity building support to help raise social investment or to bid for public service contracts. The ICRF is managed by the Social Investment Business and is arguably the policy initiative valued most by the sector.

The Social Incubator Fund is a 3-year, £10m fund that aims to help drive a robust pipeline of start-up social ventures into the social investment market by increasing focus on incubation support and attracting new incubators into the market. Incubators must raise 1:1 match funding from third-party investors to secure investment from the Social Incubator Fund. The Social Incubator Fund is managed by the BIG Fund (the non-lottery arm of the Big Lottery Fund) and has made two commitments so far.

Applicability to Australia – HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Of all the initiatives in the UK, the Investment and Contract Readiness Fund is the most transferable and will potentially have the greatest impact. The SEDIF funds have enhanced the supply of social investment, but there have been few initiatives to create demand for this finance. There has been an increase in the number of co-working spaces and other support for start-ups, but there is a gap in support between initial seed-funding and readiness to take on further investment. The Investment and Contract Readiness Fund also supports the growth of social finance intermediaries, organisations that are relatively small and scarce in Australia as compared to the UK.

2. International events – UK G8 Social Impact Investment Forum to Australia’s G20

In June 2013, the UK hosted the G8 and conducted the first side event on social investment. About 150 attendees from the eight nations joined special guests (such as Australia’s Rosemary Addis) for a day of speeches and interaction. Tweets from the event can be viewed on #G8ImpInv. Outcomes of the event were reported in a policy paper and include a global taskforce led by Sir Ronald Cohen.

Applicability to Australia – HIGHLY RECOMMENDED

Over 90 leading organisations from across the world signed an open letter congratulating the UK Government on bringing social investment to the G8. “We urge the G8 to translate the outputs of the June 6 meeting into bold action and encourage the G20 to take note and follow suit.” Australia is the host of the next G20. The G20 is a far more suitable forum for this discussion than the G8 because it includes all the emerging ‘BRICS’ economies of Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa (of these, only Russia attended the G8). The G20 also includes other countries that are doing interesting things in social investment, namely the Republic of Korea, Mexico, and Canada. This would be an opportunity for Australia to shape the international agenda and demonstrate our considerable strengths in this field.

3. Social impact measurement – the Inspiring Impact program

Inspiring Impact is a UK-wide collaboration between eight organisations to make high quality impact measurement the norm for charities and social enterprises by 2022. Over the next decade Inspiring Impact will focus on encouraging the adoption of shared approaches to measurement and on developing appropriate, affordable and accessible impact measurement data, tools and systems. The Cabinet Office is providing £100,000 to Inspiring Impact over three years, alongside support from Big Lottery Fund, The City of London, Deutsche Bank and the Diana, Princess of Wales Memorial Foundation.

Inspiring Impact is only at the beginning of its journey, but already the outcomes matrix and accompanying shared measurement frameworks are being used. If anything, their work lacks promotion and presentation, but it is excellent quality and the collaborative way this project is run encourages greater buy-in.

Applicability to Australia – RECOMMENDED INVOLVEMENT

This is an area where we can adopt many of the measurement frameworks almost without adjustment, except perhaps for Aboriginal programs, so a similar initiative would be duplicating work unnecessarily. There may be some benefit from supporting a few individuals to connect with the UK network, to disseminate and publicise materials in Australia and make any adjustments that might be necessary for the Australian context.

4. The Social Value Act

The Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 states:

(1) If a relevant authority proposes to procure or make arrangements for procuring the provision of services, or the provision of services together with the purchase or hire of goods or the carrying out of works,

(3) The authority must consider—

(a) how what is proposed to be procured might improve the economic, social and environmental well-being of the relevant area, and

(b) how, in conducting the process of procurement, it might act with a view to securing that improvement.

The Social Value Act does not actually change the procurement laws that were in place previously, but it emphasises consideration of impact beyond cost and quality of service delivered. It has been widely supported by the social sector and has empowered and encouraged social sector organisations to demonstrate their social and environmental impact when responding to tenders. It encourages the inclusion of social value in cost-benefit analyses, an area of previous confusion.

Applicability to Australia – RECOMMENDED LEGISLATION

Australia is leading in this field with the emergence of social procurement. Social procurement includes social and environmental requirements as clauses in the tender or as selection criteria and thus is clearer and more proactive in pursuing social outcomes. There is, however, still a benefit in producing an equivalent of the social value act that makes it very clear to public servants and social programs that social value for money is important to government and a real part of economic consideration.

5. Review of legal and regulatory barriers to social investment

The ‘Red Tape Challenge’ program aims to get rid of unnecessary regulation across government. The Red Tape Challenge on Social Investment was open for four months. It involved sector representatives, encouraging engagement with government and produced achievable actions that made a difference on the ground. Actions are detailed in this letter from the Minister for Civil Society and include simple, but effective steps such as “the FSA has provided a named contact to industry and other interested parties on matters relating to social investment” (p.1).

Applicability to Australia – RECOMMENDED

A similar process could engage the sector in conversations with government about how to improve the social investment opportunity. It is a cost-effective way to identify legal and regulatory barriers and anomalies and make easy, simple changes that produce a real impact.

6. Tax incentives

The UK Treasury is currently undertaking a consultation on social investment tax relief. The consultation involved the release of a paper and a tax relief consultation working group comprising 22 sector representatives. This initiative was due, in part, to the comparative disadvantages for social investment against tax relief associated with investment in venture capital. The announcement of intention has been well received by the sector, but details of what the relief will involve are not yet decided.

Applicability to Australia – RECOMMENDED AS A REVIEW

Tax incentives for social investment in Australia would encourage growth in this area. There would be benefit in combining this work with a review of the tax implications for social investors, for example the implications of financial returns from social investment by a private ancillary fund (PAF). While the UK tax code is not the same as ours, there are useful ideas in the government’s consultation paper and in responses from the sector (e.g. Social Finance’s response).

7. Social Impact Bonds and central government contribution to payments

There are about 12 social impact bonds (SIBs) operating in the UK and several more in the pipeline. The Cabinet Office has established a £20m Social Outcomes Fund which, in addition to the Big Lottery Fund’s £40m Commissioning Better Outcomes fund, will ‘top up’ payments by government agencies procuring SIBs. Applications to the funds will close mid-2016.

The £60m available will be given to average about 20% of SIB outcome payments. This sets a short term (3 yr) expectation of over £300m worth of social outcomes commitments. At the rate of current applications, there is likely to be a huge shortfall in funding distributed. Significant investment has gone into supporting the pipeline of SIBs towards the funds, including additional support for commissioners from Social Finance and the Local Government Association and the Centre for Social Impact Bonds which has developed some resources, including an encyclopaedia for SIBs, the Social Impact Bond Knowledge Box.

Applicability to Australia – RECOMMENDED FOR DISCUSSION AND STATEMENT

There may be some benefit in some agencies of the Australian Government collaborating with state governments and paying a proportion of outcomes that represents federal benefit or savings. Rather than allocate a large pot of money, an in-principle statement would encourage SIB development, set parameters and allow funding to respond to need as it arises.

8. Innovation funds for new preventative services

The £30m Department of Work and Pensions Innovation Fund is often included in discussions on SIBs, but merits separate attention here. The fund was established to improve long-term employability for disadvantaged young people. DWP did not have a history of delivering preventative programs, so wanted to spur innovation and see what providers could do. They commissioned 10 programs across the UK (there’s one in Wales, one in Scotland and eight in England) with various arrangements for social investing. Unlike other SIBs, payments are made monthly on the basis of evidence presented by program managers and is not compared to a comparison/counterfactual before payment is made. At the end of the three years of funding there will be a large evaluation of 1100 young people who have participated in the programs and about 1700 who haven’t. This evaluation will be able to compare effect sizes of the different programs and also do some sub-group analysis.

The 10 programs funded by the Innovation Fund are diverse and interesting. This a huge achievement in a space where there was previously little government funding. Program managers report that the Innovation Fund is easy to work with and that the outcomes chosen seem to be the right ones. There is some criticism that the measurement related to payments is not based on a measured improvement against a comparison group, but the trade-off is that the transaction costs associated with the set up and administration of this Fund are far less than other SIBs. The final evaluation will also measure effect robustly, however there will be no financial reward or penalty based on this measurement. The strongest criticism of this suite of programs is that there is no commitment or stated intention to implement preventative programs long term based on the evidence collected.

Applicability to Australia – RECOMMENDED IF SITUATION ARISES

The approach taken by the Innovation Fund promotes innovation and evidence-building, but is only applicable in some situations. It is best suited to areas where a bucket of funding is available for services in a new area. It is a great solution when implementing programs in the absence of well-evidenced interventions – it provides strong local evidence and innovative approaches developed in situ for further scaling and development. Impact can be captured and maximised as part of a long-term strategy.

9. A social investment wholesale bank – Big Society Capital

Big Society Capital draws its funds from unclaimed assets. In the UK, these resided with the banks. In Australia they return to the coffers of the Commonwealth but are not ring-fenced for any particular purpose. For this reason it would be difficult, although not impossible, to ring-fence these assets.

Big Society Capital was set up as a wholesale bank, providing funds to social investment finance intermediaries (SIFIs) that provide affordable finance to social organisations. It does not invest in the front line. Difficulties include:

- The lack of places to keep the bulk of funds until they are invested i.e. Coop Bank? Capital markets?

- The difficulty of achieving a 6% return in an emerging market

- The relationship with and demands of the banks – see Merlin agreement

- The mismatch between the size of the loan social organisations want and the size of investment it is cost-effective for SIFIs to make

- That social finance can be more expensive and restrictive than commercial finance

- The argument that early stage social enterprises need equity, not debt

For more insight see David Floyd’s analysis of Big Society Capital at two years and his February interview with Nick O’Donohoe.

Applicability to Australia – NOT RECOMMENDED

Social organisations in Australia appear to have a smaller appetite for debt and are more easily able to access grant-funding. There are also fewer SIFIs in Australia than in the UK. Loan finance is available through the SEDIF funds, but these suffered due to a lack of demand from investment-ready organisations. Big Society Capital hasn’t provided all debt. It has taken some equity stakes and in some cases has taken over organisations similar to a private equity firm. It has also invested in Social Impact Bonds.

Update June 2014 – the three SEDIF recipients have increased their volume and frequency of loans in 2014, such that demand for funds may soon outstrip supply. This may suggest a role for a wholesale social investment bank in Australia, although the constraints and interest rate required would need to be set appropriately for the Australian context.

10. Funds for social ventures/enterprises

All funds have struggled with a lack of demand for loan finance. The Bridges Fund was launched in August 2009 and has raised £12m. In its first three years of operation, however, it committed only a third of that. An early evaluation of the SEIF fund found that “A large majority of the fund was used as grants, raising questions over the demand for loan finance amongst social enterprises and charities in the health and social care sector.” A National Audit Office report states that the fund faced considerable underspend and had committed the majority of its funds as grants, rather than loans.

Applicability to Australia – NOT RECOMMENDED AT THIS STAGE

The major Australian Government initiative in the social investment space has been the establishment and matched funding of the Social Enterprise Development and Investment Funds (SEDIF). These have been well-received by the sector and have attracted international attention. However, each of these three funds has had some difficulty making loans due to a lack of demand. This seems to be consistent with experience in the UK and does not suggest a demand for further loan finance.

Reference

Cabinet Office (2012) Growing the social investment market: HMG social investment initiatives.