(Social Finance, Towards a New Social Economy, 2010)

(Social Finance, Towards a New Social Economy, 2010)

During a recent lecture on social impact bonds for the Saïd Business School’s Executive Education Impact Investing course, one of the students asked me, “Am I already part of a social impact bond?”

Social impact bonds (SIBs) are a new construct, with the term coined in 2008 and the concept piloted by Social Finance in Peterborough in 2010. But arrangements that fit our current understanding of SIBs already existed and continue to operate. For organisations involved in these arrangements, the benefits and challenges of identifying with the SIB phenomenon will determine whether or not they associate themselves with the term.

The lady who asked the question was running a non-profit organisation that had an outcomes-based contract with the Louisiana State Government to provide a service. A loan from a local finance institution helped to cover their working capital.

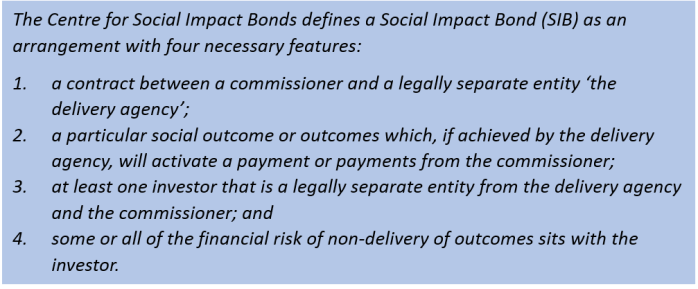

In order to examine whether she was indeed part of a SIB, we turned to the Cabinet Office definition.

In this arrangement, the first two conditions were certainly met.

To determine whether the third was, we examined whether her creditor could be considered an investor. Her organisation existed for the purpose of providing the service and the contract accounted for the entirety of their service provision. The loan was made on the basis of this single contract with government. The lender was a legally separate entity from both the non-profit and the government. So it looked like her creditor could be considered an investor.

The fourth condition relates to the financial risk of the investor. Was the finance institution truly taking on any financial risk? Indeed, there were two distinct types of financial risk taken on in this situation. Firstly, there was the risk of non-performance; that the non-profit would fail to deliver the results that would trigger payment from government. Secondly, there was ‘appropriations risk’, the risk that government doesn’t approve the payment of a previously agreed contract [1]. If the non-profit, for either of these reasons, did not receive sufficient funds from the government to pay the loan, they would become insolvent and the finance institution would not have the loan repaid. So the fourth condition was met.

This non-profit was certainly part of a social impact bond as defined by the UK Cabinet Office, although none of the parties involved were using the term.

Other examples that may meet the definition of a SIB but not identify with the term include charter schools, which are independently run with three year contracts based on outcomes. If they establish a bridge loan fund to cover the cash flow gap, they may meet the four necessary criteria. These bridge loans are often used for capital infrastructure spend and the financial risk for the lender is sometimes rated, so certainly exists.

Implications

- When we assess SIBs and compile data or ‘track record’, it may be worth looking at these existing arrangements that fit the SIB definition.

- Organisations that are part of arrangements that fit the SIB definition might consider the benefits and challenges associated with the SIB label (e.g. will appropriation and other payment risks be reduced if the contract is ‘announced’ as a SIB).

- The Cabinet Office definition came after several SIBs had already been developed and was not written by the Social Finance visionaries responsible for articulating and implementing the original concept. Does it misrepresent the concept? If so, do we need to change the definition?

[1] Appropriations risk is a feature of the US governmental systems and is described by Steve Goldberg in his fourth SIB Trib: “Even if a state signs a valid contract calling for the payment of money, it doesn’t (indeed, can’t) pay what the contract says it owes unless and until the state adopts an appropriation law specifically and affirmatively authorizing the expenditure. What’s more, legislative authority to appropriate funds only lasts as long as the state’s constitution allows budgets to remain in force. In most states that’s one year, in some, two. So not only does a state have to enact budget legislation and then pass separate appropriations bills to legally spend any money, they can only do the latter within the one- to two-year time horizon of the former” (Goldberg, 2013).